Gorogoa and laying the groundwork

The kind of game I had in mind when I started Backlog

Gorogoa has been on my personal backlog for many years. It’s the kind of thing I started Backlog for: A game I’ve been eyeing now and again, thinking to myself that I’d eventually find the time, remembering vaguely the critical response to it, the podcasts I’d listened to where it was mentioned in reference to other games I’ve enjoyed, and, in the particular case of Gorogoa, that big, colorful monster eye that has stared out at me, waiting and watchful, since the game released in 2017.

Now, finally, six or so years later, I’ve gotten around to it.

I love puzzle games (see my recent reviews of Viewfinder and Cocoon for Polygon). I find them to be uniquely authored experiences, by which I mean, when playing them, I can feel the influence of another mind at work, laying out before me the clues necessary to come to a conclusion they’ve already designed. This feels especially true of those rare, single-developer games, where you are, quite literally, interacting with another mind, but it feels true of even larger team projects, where the cohesive vision of a group of people comes together to communicate a single idea.

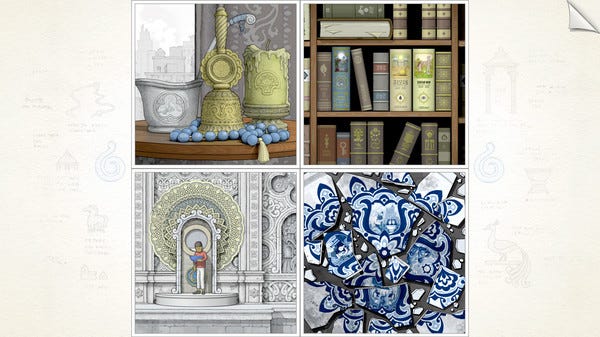

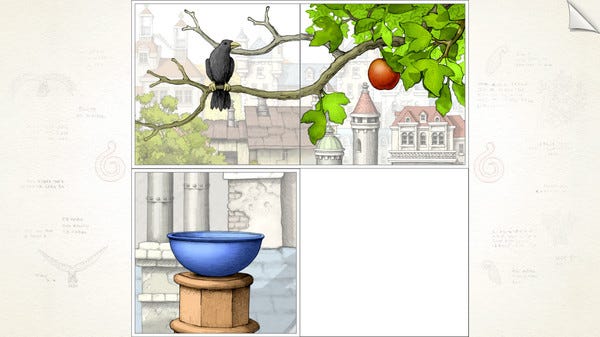

Gorogoa is one of those single developer games, though, and it shows. The gameplay is simple in practice but hard to describe. Taking clear inspiration from the panels of comics and graphic novels, the player is presented with four squares at a time, each with its own content and interactive elements. Clicking within an individual square might zoom in on a particular object. A bowl of fruit or a staircase. Elsewhere you might be able to pan right or left, each panel an old-school adventure game in miniature. At all times, the player can move each square to a different quadrant, sometimes shaking loose elements within that scene, creating a window out of a door or a ball out of a sun (or a sun out of a ball) that you can then transpose onto a different square.

I did say it was hard to describe.

Thinking of the game as a window is the best way to approach it. Beyond the fact that the gameplay space looks like a four-paned window, you often find the character—presented at various stages of his life, from youth to old age—looking out a window or sitting beside one. Gorogoa is a game about second glances, about reconsidering the micro within the macro and vice versa. It invites you, from your life, to look into it. Gorogoa asks the player to consider: What am I looking at, and what I have I missed?

I liked but didn’t love Gorogoa. I felt faintly disappointed when I finished the game, if only because I had built it up for so long in my mind. Video essays like Jacob Geller’s “Gorogoa and the Nature of Time” have convinced me of the depth within the game’s wordless narrative, but I must confess that I didn’t feel what Geller and others felt while I was playing. My time with Gorogoa felt mechanically pleasant, but narratively lackluster. Besides a vague but pleasant vibe, I just wasn’t picking up what it was putting down. Just as soon as I finished it, I felt it receding from memory. It felt like a fun trinket. A novelty, not a mainstay.

Still, I’m glad to have played it. There is something about going back to a game that’s fallen out of the zeitgeist, something that no one would fault you for not having played, and yet there you are, playing it. It’s a funny thing that feels unique to gaming. If I were to read a six-year-old book, or even a twenty-year-old one, nobody would bat an eyelash. It’s only games that get washed away so quickly by our demands for newness.

I now have a greater appreciation for the games that have gone on to iterate on what made Gorogoa great. Hell, an argument could be made that Viewfinder or Superliminal were 3D takes on this very same concept. In this way, playing Gorogoa was a bit like listening to my favorite artist’s favorite artist. It might not be my thing, but I can see why it’s theirs. And because I like their stuff, I’m grateful that they liked this stuff enough to iterate on it.

If Gorogoa is about second glances, for these reasons alone, I’m glad I looked back and played it. And who knows? Maybe I’ll do it again. To see things anew, again.