Octopath Traveler II and who gets to be the protagonist

A game for people who wonder what the shopkeeper's deal is

True story: I’ve tried more than five times to write a short story from the perspective of a shopkeeper in an RPG.

Though it’s been a while since I published any fiction, I’ve got a thing for odd angles on games and the characters that inhabit them. I also have a thing for thinking about work in fiction, interactive or otherwise. But why a shopkeeper, you may ask? Answer: They seem to me the most workaday citizens of your standard RPG, and thus worthy of empathy, which is to say, worthy of exploring fictively. So when Octopath Traveler II introduced a mechanic to see the innermost thoughts of your garden variety potion seller in each and every town, trust me when I say I read them all in this 70+ hour journey.

I have this undercooked notion that short stories are a more honest form of storytelling than the novel, in that they privilege the episodic over the epic, arguing that meaning, in art as in life, is experienced in moments of crystallized ambiguity rather than a definitive sweep of surety one views from a great distance.1 That’s all a highfalutin way of saying I usually prefer reading short stories to novels, so when Mike Mahardy over at Polygon called Octopath Traveler II a “short story collection video game,” I ran, not walked, to Steam and purchased the thing at full price.

Back when Backlog was a mere babe, I called What Remains of Edith Finch a novel-in-stories, and at the risk of playing the hits, I think that same literary moniker applies, at least in structure, to Octopath as well. You play as eight different characters, each of whom has a distinct story arc that, for the most part, does not intersect with the others. They do, however, share a world, and, though I did not have the energy to pursue it,2 there appears to be an optional endgame quest where all their stories begin to overlap. However, for the vast majority of the experience (those 70+ hours I mentioned), what you are playing here are eight arcs that have their own concerns, their own plot beats, and their own distinct tones.

Are they particularly good stories? Eh. They’re all very pulpy, I can say that much, but usually in a self-conscious way that calls attention to itself when the game is troping for troping’s sake. Perhaps if Zelda had not come out and demanded the entirety of my free time, I would’ve pursued the final threading of the narratives, though, from what I’ve read online, it sounds pretty tropetastic, in the vein of the rest of the game. To be honest, though, I mostly stopped playing because such a convergence of stories felt antithetical to what I’d come to enjoy about Octopath, which was how everyone—everyone—in this game had their own story.

Primarily, of course, I’m speaking of the central cast of eight. Bouncing between their siloed-off stories was novelty enough, especially as I’d never played the original. I appreciated their range in tone, with some sillier moments (an opera singer with ulterior motives; a rampantly socialist merchant having to fight off venture capitalists to share the means of production) to balance out the more self-serious (an evil brother taking the throne by way of patricide; some gross lineage related stuff for a character sold as a child into a crime syndicate). There’s even a prison break sequence! I can’t say any individual story was wholly original or all that impactful. Rather, they felt like comforting remixes of things you’ve seen in many RPGs many times over. (Yes, one character does suffer from amnesia. How did you know?)

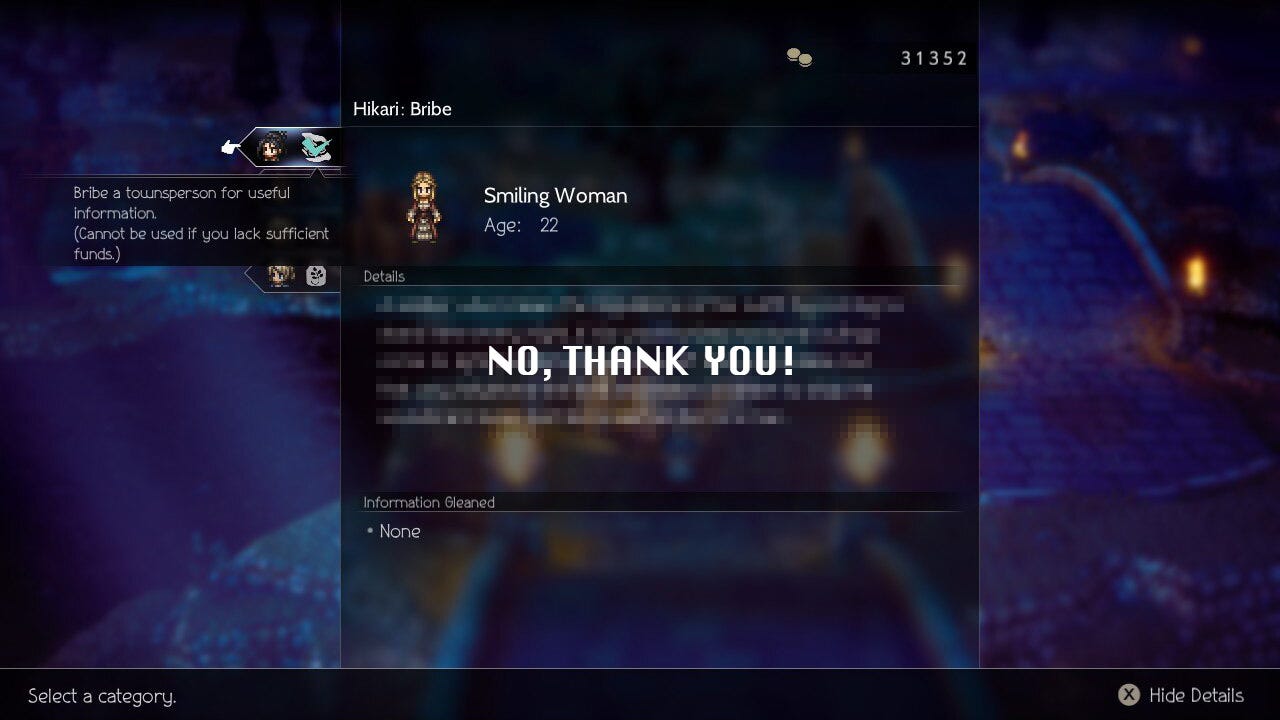

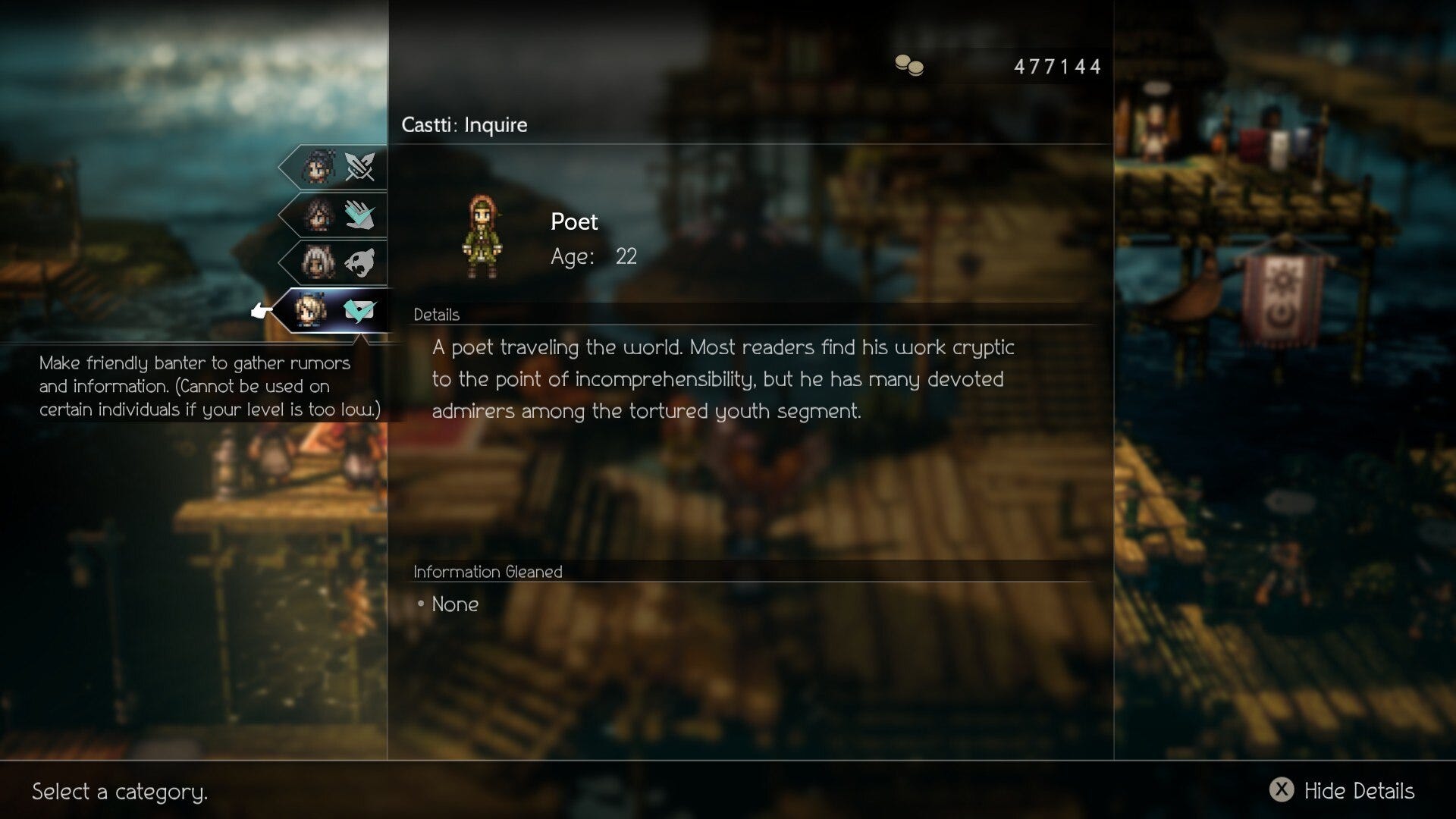

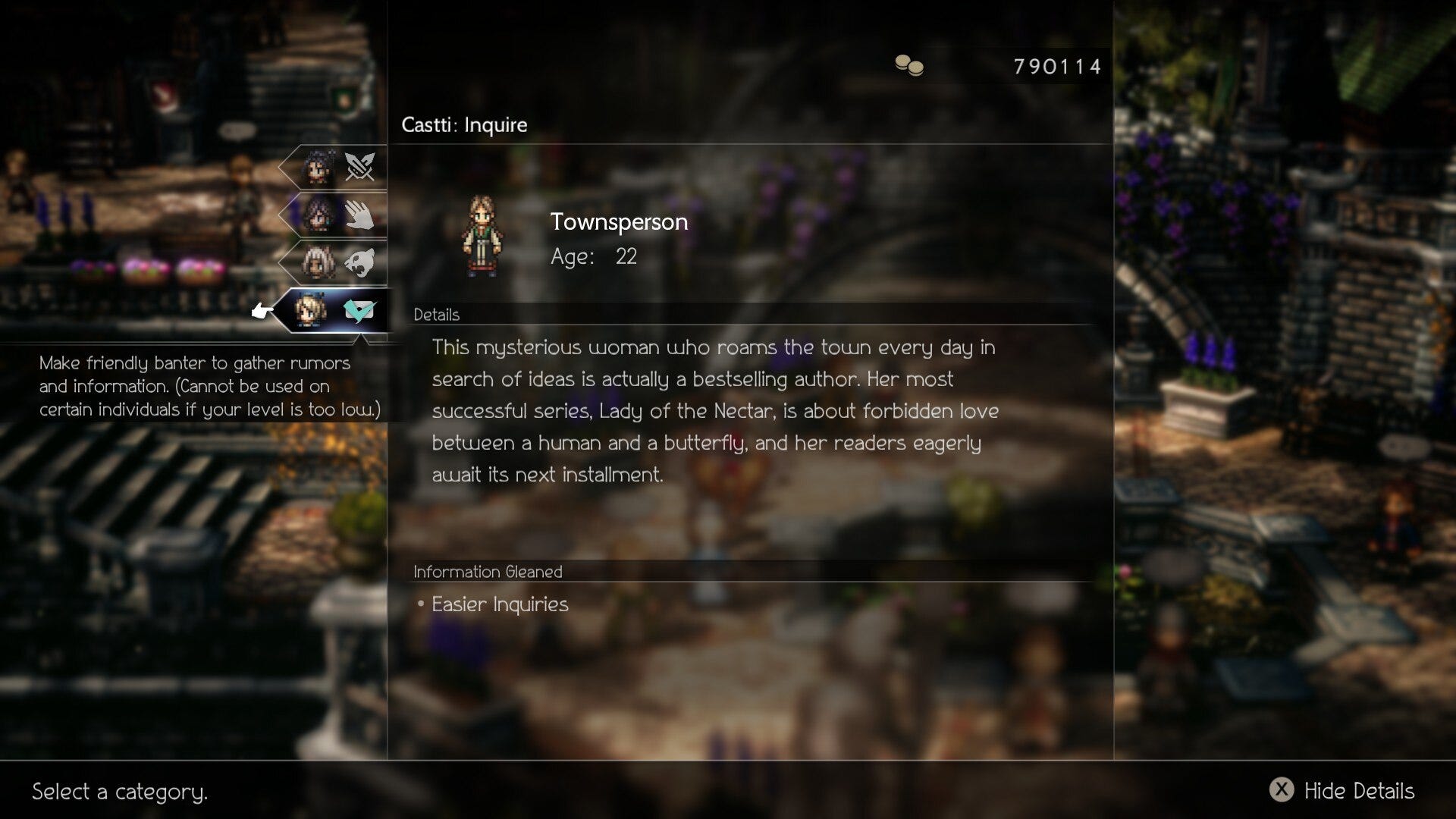

But it isn’t just the protagonists who are afforded their own time in the spotlight. Throughout the game I found myself keeping the apothecary Castti in my party, as she had the simplest mechanic for reading NPC backstories. In terms of mechanical rewards, looking at a random child’s backstory, for example, might net you a slight discount at the inn or the occasional hidden item. But narratively, I found that they made the world feel more alive, not simply with lore, but with lives.

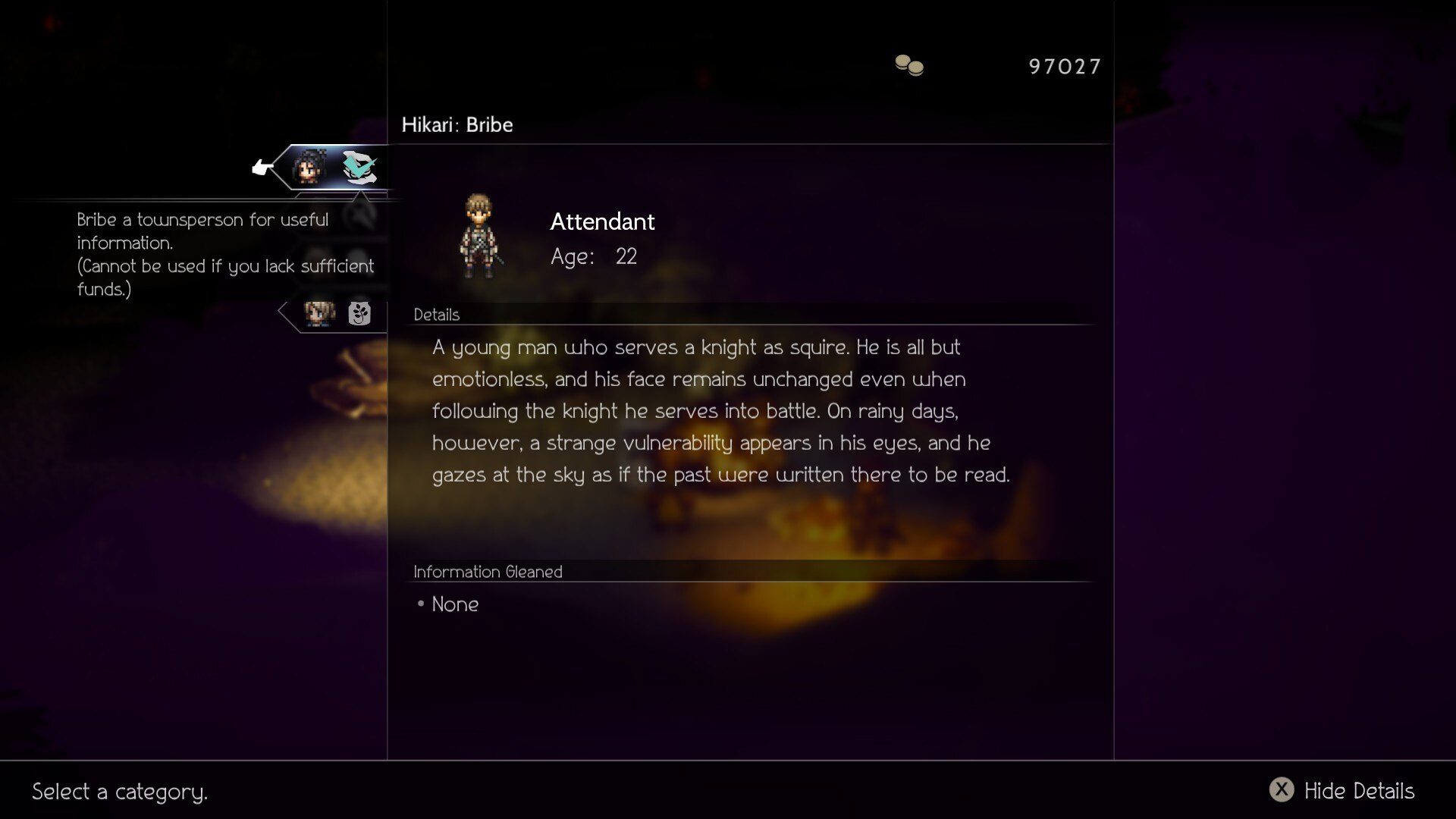

Maybe you don’t wonder, as I do, what a random RPG townsperson does when they’re not selling you potions. But if you do, Octopath Traveler II is the game for you. A prison guard whose cruelty stems from his own sense of inadequacy and powerlessness in life? That’s in there. A lovingly crafted example of vulnerability in an otherwise unemotional squire? That, too. A random townsperson who wrote a series of novels about the Lady of Nectar, whose forbidden love with a butterfly (??) has captivated readers? Uh. Sure, yeah, why not?3

Do these little paragraphs make Octopath Traveler II a modern classic? Absolutely not. This is a long game with occasional dips in quality across its many stories. The highs are high, but the lows are low. (The dancer Agnea’s story for me was simply too one-note, relying on a painful repetition of wanting to make people smile, all while her cohort was dealing with heretical conspiracies and multinational political conflicts.)

But what Octopath does have is ambition. Ambition to tell so many stories it couldn’t possibly close every thread. Ambition to try something antithetical to the very nature of RPGs, which so often tell the player they’re the special chosen one, which, on its face, can be a dangerous narrative to imbibe.

Octopath Traveler II instead tells what I believe to be the truth. That your story is just one among many. That everyone is going through something, and it’s up to you to listen.

This is highly, highly reductive, and probably outright wrong, I know. But this is my videogame newsletter, okay? ↩

Was it wise to play such a long game in the lead-up to Tears of the Kingdom’s release? No. No it was not. ↩

It’s not all good, I feel the need to note. Random sexism abounds, and I definitely encountered some inexplicable transphobia in one of these bios, which, in addition to being hateful, was just not original, as hateful things tend to be. ↩